Mount Rainier via the DC

Two day climb of the classic Disappointment Cleaver

Arguably the most impressive mountain in the United States outside of Alaska, Mount Rainier dominates its surroundings in a way that you really have to see in person to understand. The highest peak in Washington state and the Cascade Range rises to 14,411 feet from practically sea level, is more topographically prominent than K2, and has the largest glaciers in the lower 48. Needless to say, summitting Rainier has been a bucket-list item for me ever since I started mountaineering.

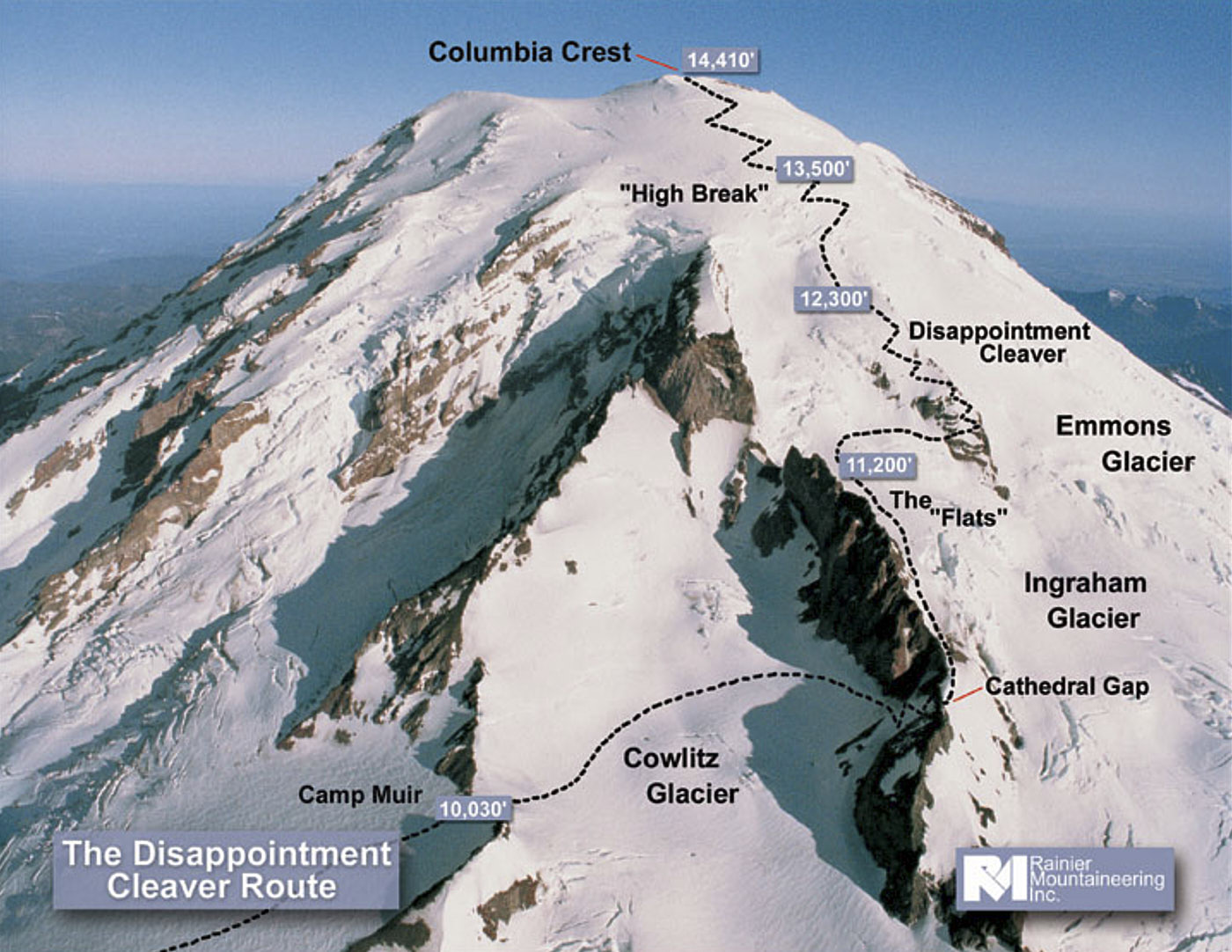

Back in March, I made plans with Tim and Taylor to attempt Rainier via the Disappointment Cleaver, the standard route to the summit. Since the DC is heavily trafficked by mountain guides and their clients, there’s basically no need to navigate or break trail. The tradeoff is that you shouldn’t expect a lot of solitude on the route. But despite being the easiest route on Rainier, the DC is not “easy”; it’s still a 9,000 foot glacier climb with real objective hazards. I was happy to have built experience climbing smaller glaciated peaks last summer before attempting this one.

Climbing Rainier comes with a bit more red tape than the average Washington mountain, and it pays to plan ahead. The important permit to secure in advance is the wilderness camping permit, especially on weekends (more information here).

Climb Day 1

After picking up our climbing permit from the somewhat hard-to-find Wilderness Information Center on Saturday, we left Paradise at 10:30am to start the 4,000 foot hike to camp. This part of the route is non-technical and follows well-maintained trails (partially snow-covered this time of year) up to Panorama Point before slogging endlessly up the Muir Snowfield. Lots of dayhikers and other climbers were out enjoying the good weather.

The most common and well-known camp on the DC route is Camp Muir, but it was booked out for the weekend. Our permit required us to camp on the Muir Snowfield at least 500 vertical feet below. We decided to camp at the upper boundary of this zone, by Anvil Rock. As it turned out, no one else was camped at Anvil Rock and it also had better views than Muir in my opinion. It was nice to get some time away from the crowds and I would totally recommend Anvil Rock as an alternative to Camp Muir on the DC.

We spent most of the afternoon alternating between napping, taking pictures, and melting snow for the summit push on Sunday. Tim and Taylor already had some mild altitude symptoms (dizziness and nausea, respectively), so we focused on resting and hydrating. Tim popped an ibuprofen which seemed to clear up his symptoms.

Climb Day 2

We started our summit push on Sunday at around 2am. In choosing our start time, we tried to strike a balance between not getting too cold near the summit (for which a later start is better), and mitigating objective hazards like rock/icefall and snowbridge collapses (for which cooler temperatures and an earlier start are better). The weather forecast was for around 15F at the summit, which I thought would be pretty cold. But in hindsight, we probably could have started earlier since the summit didn’t feel very cold at all; the strong sun and low winds helped.

We made the short hike to Camp Muir, which marks the start of the glacier travel, and roped up for crossing the Cowlitz. The Cowlitz traverse was fairly mellow with only a few hairline crevasses to step over.

Although most of the remaining route is on glaciers, two sections are on rock: Cathedral Gap and Disappointment Cleaver. These sections are kind of inconvenient because glacier gear like crampons, ice axes, and rope become clunky and even dangerous. In particular, it’s not advised to keep a long rope interval due to the likelihood of flossing loose rocks down onto other parties. For Cathedral Gap, we shortened the rope to keep it up off the ground but kept our crampons on to save transition time.

After crossing Cathedral Gap we lengthened the rope again for the Ingraham Glacier. The route up the Ingraham climbs past some monster crevasses and snowbridge crossings before leveling out at Ingraham Flats camp at 11,200 feet. We stopped for a break here.

Our next job was to get onto the namesake of the route, the Disappointment Cleaver. This part involves traversing through the “Icebox” and “Bowling Alley”. As the names suggest, these sections have the most serious icefall and rockfall hazards of the route from overhead seracs and loose cliffs, so we focused on moving quickly without stopping.

The Cleaver involved about 1000 vertical feet of class 2 scrambling up loose rock with some occasional class 3 moves. Instead of short-roping, we decided to remove the rope entirely which made things go much faster.

The DC tops out at around 12,000 feet, still 2,000 feet below the summit. There’s not much to remark about this part other than that it was a long, slow slog at altitude. In addition to slowing down, I had some dizziness and headache, while Taylor was feeling nauseous again and threw up just a few hundred feet below the summit. Tim, however, had prophylactically popped another ibuprofen in the morning and was doing fine. I might have to try that next time!

We topped out Columbia Crest at around 9am. Rainier’s summit area is huge and flat, and it’s so much higher than the surrounding terrain that everything kind of blends together! Nevertheless, it was quite cool to be in the summit crater after seeing only pictures of it for the last few years. A couple snowy humps looked like they could be the true summit and we tagged them both to be sure.

We were still feeling kind of bad from the altitude, so we didn’t linger too long before starting our descent. Going downhill at altitude went much faster than uphill, though we still had quite a few crevasse crossings, snow-rock-snow transitions, and overhead hazards to manage which took a lot of energy in the heat of the day. It was a great relief to finally reach Camp Muir, which marked the end of the danger zone.

After packing up our camp at Anvil Rock, the descent went blissfully quickly, practically running down Muir Snowfield freed from the rope. It took us only about an hour and a half to get back to Paradise.

Looking back at the thing we climbed from the trails near Paradise. Somehow it's hard to imagine we were on the summit in the morning.

Thanks to Tim and Taylor for a great trip! Climbing Rainier marks the completion of the 5 Washington volcanoes for me and Tim, a journey which started with St. Helens back in April 2021.